22/11/2022

OPENING THE SCRIPTURES

Beginning with Moses and all the prophets, Jesus interpreted to them the things about himself in all the Scriptures (Luke 24.27).

These are the very well-known words at the heart of the much-loved story of the walk to Emmaus on the evening of the first Easter day when Jesus, as yet unrecognised, comes along side Cleopas and his companion and listens to what they have to say.

And this is probably the first and most important, and perhaps slightly surprising, thing to say about how we open the Scriptures today, particularly for those who don't know them and in order to see how they speak to the issues and challenges of our day - Jesus listens before he speaks.

His first words are not, ‘I have risen from the dead’, nor even some credal explanation of the meaning of death and resurrection, but quite the opposite; he asks them what they are discussing as they walk along.

And by the way, we tend to miss the humour in scripture; but Luke, the consummate storyteller, tells this next bit with a witty flourish. ‘Are you the only stranger in Jerusalem who doesn't know the things that have taken place there in these days’, says Cleopas.

‘Oh, what things?’, replies Jesus.

As if he doesn't know what's been happening. It has, after all, been quite a weekend.

But Jesus wants to listen. Jesus needs to listen. He needs to understand what it is about what has happened that they are unable to understand. For they have all the facts and the information they need.

They know about Jesus of Nazareth. They know he was a prophet mighty in Word and deed. They know he was handed over to death and was crucified. They hoped he was the one to redeem Israel. And they are saying all this to him, the Risen Christ. Why, they even go on to tell him about the resurrection. It's the third day since these things happened, and some women from our group went to the tomb early this morning and his body wasn't there, and they came back and told us about some crazy vision of angels who said he was alive. Then some of us – who I presume must mean the sensible men in the group - went to the tomb. They found it empty as well.

They have all the facts. They have all the information. But it is not good news for them. They are unable to piece the story together and make sense of it and there is a reason for this. And it's a simple one. Their own considered and informed understanding of the Scriptures, by which of course we mean the Hebrew Scriptures (what we call the Old Testament), didn't allow them to believe or imagine a Messiah could suffer. So, yes, they had indeed hoped Jesus would be the one who would redeem Israel, and they imagined and believed him to be a Messiah, rather like King David, a conquering hero who would kick out the Romans and establish a new Jewish kingdom, and therefore, when Jesus was crucified it was, for them, the crucifixion itself that was the problem. It kind of proved that Jesus couldn't be the Messiah, because the true Messiah would not have gone and got himself killed like this.

Indeed, he had an opportunity to prove and demonstrate he was the Messiah, but he didn't take it.

And, therefore, the crowd who jeered him turned out to be right. “If you are the saviour save yourself”.

But he couldn't. Therefore, he wasn't.

So disconsolate, and confused, and feeling stupid, (and maybe worrying that what happened to Jesus might happen to them), they are getting out of Jerusalem while the going is good. And they are not in a position where they could recognise Jesus. Even when he is standing next to them. He is, to their certain knowledge, dead. And buried. And all the stories that they’ve heard, can't change the theological conviction that is closing their eyes. Though, as a footnote, we might also hear the beauty and craft of Luke’s storytelling, for in saying that their eyes are closed, Luke also implies that somehow God was the one who was doing the closing and that their inability to recognise Jesus wasn't just about their lack of faith or lack of theological imagination, but was part of the mystery of how each of us comes to know Jesus, which is about love. God’s love for us in Jesus Christ and then the response of our love to God’s love. And for this to happen their theological imagination needs to be rekindled.

And this is what Jesus does.

‘You foolish men’, he says with a smile, ‘how slow to believe’. Then beginning with Moses and all the prophets he interprets to them the things about himself in all the Scriptures. In other words, Jesus revisits the Scriptures, the scriptures that they know so well, to show them that there were other ways of understanding them and therefore other ways of being Messiah.

The challenge for us is that we also need to continually revisit Scripture in order to understand it and have our understanding renewed.

Biblical scholars often explain how interpretation of Scripture has changed in their lifetime. The well-known Old Testament scholar, Walter Brueggemann, writes of the move from historical criticism to social-scientific criticism. This invited those of us that engage with the bible today to enter into the ‘alternative worlds’ that the biblical texts create.

It invites a change in perspective, a different priority perhaps. Throughout Scripture we hear God calling his people to live in a radically different way to the status quo. The prophets again and again challenge those with power, those who are exploiting the poor and the weak and the marginalised.

So, I invite you to engage imaginatively with the biblical texts. They are meant to give wisdom and courage, to give hope. When the disciples took their literal interpretation of the coming Messiah who would be King of the Jews, they lacked the imagination to think about this in a radically different way. They needed to reframe their previous understanding of well-known and much-loved texts.

We must not repeat their mistakes! It is too easy to think that because we have Jesus’ reinterpretation of the Old Testament, because we read the Old Testament in the light of the New Testament, that we get what he was saying. But we then run into the danger that we don’t understand just how counter-cultural and radical Jesus was in his ministry and his teaching.

And when we lose sight of this, we can’t be radical and counter-cultural in the way we live and in the way we preach. So again and again, we need to take a look at the lenses through which we are reading Scripture. When we read the text, we need to be both suspicious and curious, and not take the meaning for granted; and we need to be both suspicious and curious about own understanding of the text because of course we are influenced by our context and our teachers.1

We read scripture in dialogue - with the text itself, of course, but also with each other and with Christians down through the ages.

In so doing we are invited to imagine a different reality, a reality rooted in the mercy, justice and kindness of God. Such a theology of imagination invites us to engage with the world in a different way by imagining the way the world can be, the way God might want it to be. And the way we understand how God might want it to be is by spending time with God, praying as well as reading and studying the scriptures, knowing them intimately, reading them with others, opening ourselves to the guiding of the Spirit.

William T. Cavanaugh, a political theologian, writes in his book on Chile under Pinochet about the force of what he calls liturgical imagination, where gathering to celebrate the Eucharist subverted the political reality that attempted to destroy community.2 He quotes at length from the novel Imagining Argentina by Lawrence Thornton. The protagonist, Carlos Rueda, is visited with a peculiar miraculous gift, the capacity to create futures by acts of anticipatory imagination.

So, by his stories men appear in the middle of the night to give back babies, holes open in solid concrete walls and tortured prisoners walk to freedom. His imagination finds people who have disappeared.

But his friends struggle with this – they are convinced that Carlos can’t confront tanks with stories, helicopters with mere imagination. They can only see the conflict in terms of fantasy versus reality. Carlos, on the other hand, grasps that the contest isn’t between imagination and reality, but between two types of imagination – that of the regime and the dictators, and that of their opponents. Although the friends remember a time before the regime, they are too scared to let their imaginations take them beyond memory. Hoping for a different future has become too painful.3

So, we need to allow our memory, and our engagement with Scripture, to invite us to imagine a different reality through what it is telling us about the past. We therefore don’t read all Scripture literally, we read it by imagining the reality into which it spoke – the creation narratives, the Exodus, the challenges of the prophets, and then story of the birth of Jesus, his life and teaching, his crucifixion, his resurrection, the means whereby God reimagines and recreates the whole world.

We engage with the poetry and the law and the history, asking what different representations of God they offer and how these representations challenge the imagination; we read texts which refer to history as well as to philosophy, inviting us to know God through creation, through what is morally right, through knowing the will of God.

Imagination invites us to return to that which we know, to reinterpret it, to wrestle with it, to ask questions of it, to apply it to our context and to then allow it to reimagine our future.

John McIntyre4 wrote a lot about theology and imagination – he unpacks how Jesus uses parables and stories and imagery to draw on what the crowds knew of Scripture and to invite them to contemplate, to imagine, a reinterpretation of Scripture, thereby imagining a different future.

So, with this in mind, let us return to where we started, on the road to Emmaus.

I already mentioned how Jesus doesn’t jump in to teach (after all, how could these disciples, his friends, not recognise him?) but he questions them, he listens. He needs to know what they have seen and heard and how they’ve interpreted it, so that he can confront their imagined future with a different way of thinking.

I guess I'm not the only preacher who down the years has sometimes dared the hermeneutical presumption to reconstruct what Jesus did eventually say, when he began to talk and ‘open the scriptures’.

Well, we know he started with Moses. Perhaps speaking about the night of the Exodus and the blood of the sacrificed lambs painted on the lintel of the doors and the angel of death passing over. About how God had made a covenant with his people that night but like all the other covenants God had made we had failed to keep it, going our own way, hedging our bets, putting our trust in ourselves.

He would have spoken of how all the prophets railed against this disobedience, but it made no difference. Then one of them, Isaiah, had had this astonishing and imaginative vision of a servant, someone coming from God who would suffer on behalf of the people and carry their infirmities, be wounded for their transgressions, crushed for their iniquities.

Or maybe going further back, to the covenant with Abraham, drawing the disparate threads of the tapestry of scripture into a new picture, of how God asked him to sacrifice his own son Isaac; and they went up the mountain, and Isaac said to his Father, ‘Father, we have kindled a fire…we have a knife to make the sacrifice, but where is the lamb for the burnt offering? And Abraham replied, ‘God will provide the lamb for the offering, my son.’ And, binding his son and laying him on the wood, heard an angel telling him to spare the boy, and saw a ram caught by its horns in a thicket, offered it instead. And we always thought that when Abraham said God will provide the lamb, he was referring to that ram which he found when his faithfulness to God was proved true, but it wasn’t. And neither does it just refer to the lambs that were slain on the night of the Exodus. And neither does it refer to the lambs that we slay year after year, Passover after Passover, because, in the end, the blood of lambs and bulls and goats cannot take away sin. They are not pleasing to God. They don’t work.

And the prophet Micah spoke very plainly about what God wanted. Was it burnt offerings? Or thousands of rams? Or rivers of oil? The sacrifice of a first born for the atonement of your own sins? No, what God requires is this: ‘To do justice, to love kindness and to walk humbly with God.

Here was the point. God and only God could provide the sacrifice, a life perfectly offered.

The Messiah had to suffer, because the Messiah was never going to be an earthly ruler, another David ushering in another human kingdom.

It was about the rule of God. So, God had to enter the situation himself. Had to take the risk of being rejected; had to be that Lamb of God that we could not offer and that we could not become. The Messiah had to suffer because we suffer.

How could we ever know God’s love if God was always beyond us?

How could it be real if it was always the other side of all our suffering and dying?

We needed a Messiah who was like us in every respect, one of us, and yet without the sinfulness that kept on meaning we got it wrong.

Therefore, he came in the very likeness of our fragile flesh, subject to its constraints and demands, and especially its pains. But he would be obedient. Even to death. He would live a life of perfect offering to God and perfect communion with God.

He would, in this sense, carry the sins of the world. He would be the embodiment of God’s people and live out perfectly the life of offering we had failed to live. At the same time, he would show us the depths and the extent of God's love. He would, in that sense, be paying the price that none of us could pay.

Do you remember Hosea saying that when Israel was a child, I loved him. that I led him with bands of love, with cords of kindness like one who tenderly lifts a little child to its cheek. That is how God loves his people. That is how God loves his world. God will never give up on us. He will go on loving even if we never recognise him or accept him. There is nothing that can separate us from God’s love.

But such a love can only be real if it is offered freely. That is what the Messiah does, the Messiah who suffers. And likewise, love can only be real if it is returned with the same freedom with which it is offered.

God will not force himself upon you. God will not twist your arm. God will not play dice with you.

God is steadfast, faithful, enduring. What God wants is a relationship of love. God’s covenant was always a marriage proposal, not a court order!

That was the reason the Messiah had to suffer. Because it was love.

Don’t you remember what he said: When I am lifted up, I will draw all people to myself? That there is no greater love than this, that one should lay down one’s life for one’s friends. That is what he did. That was the reason he suffered.5

Well, forgive the presumption, but that is the sort of thing I imagine Jesus said on the Emmaus Road. Well, something like that!

Jesus doesn't give them new information. He gives them a new interpretation. And the new interpretation speaks directly - with kindness and clarity - to the precise questions, objections and difficulties they have with understanding Jesus’ death and what it meant for them to be his followers, people who have to carry his cross as well.

And of course, we see this pattern throughout the gospels and also in the teaching and preaching of the early church. Jesus nearly always listens before he speaks. He is always asking probing questions, drawing out from us the things that really matter and therefore speaking to us with that same sharp and challenging clarity.

But also, in the Acts of the Apostles; what Paul says in Athens is markedly different to what he says in Corinth. This is because the contexts are different, and the questions are different.

It is the same gospel, but it is never reduced to a package to be handed on. It is always a relationship to be imaginatively drawn into.

Beginning with people’s questions and concerns, we need to open the Scriptures in the same way. Perhaps questions about the Scriptures themselves, what they are, and how we understand them.

But more probably the questions that emerge from life itself. And while it is unlikely that many people nowadays will say to us, ‘Well, I would believe in the Christian faith, but I just can't understand why the Messiah had to suffer and die; and the events surrounding his crucifixion just doesn't line up with my understanding of 8th century Hebrew prophecy’, what they might say to us – and it is not necessarily so different – is ‘Why is there such suffering in the world?’ and ‘Why doesn't God just speak to us clearly and plainly?’ and ‘How are we going to find generous and sustainable ways of living in the Earth?’ and ‘How we are to resolve different understandings of scripture when we address issues of gender identity and human sexuality?’

And beginning with… well, to answer the question of suffering we might begin with the story of Jesus’ own suffering and show how the God that we believe in is not distant and separate from the suffering of the world; and to answer the question of why God doesn't speak to us clearly and plainly we might turn to the resurrection stories and show how Jesus himself, even on the day of resurrection, isn't recognised, not because he is making it difficult for us, but because what he wants is love, and for it to be love it has to be free and this too speaks into the story about suffering because this may be the only universe we can have where there is freedom and where there is love; and to answer probably the greatest and most pressing question of our day about how we are to live sustainably on the Earth we might turn to the story of creation where God makes us stewards of the Earth, or to the book of Leviticus where we are told there should be a sabbath rest for the land, or to the Lord's prayer itself where Jesus asks us to pray for enough each day and not to ask or expect more than our share; and to address questions of gender and sexuality, we can point to the texts that speak of the marvel that is the human being, so much so that God became flesh, therefore breaking down the duality of so-called spirit and so-called flesh, rejoicing in the wholeness of the human body and the body as the temple of God, deserving to always be treated with dignity and respect.

And in order to open the Scriptures in this way, we need to know and love the Scriptures.

We need to ask the Holy Spirit to rekindle and expand our theological imagination. We need to be good listeners so that we might begin to speak with that charity and clarity that we find in Jesus.

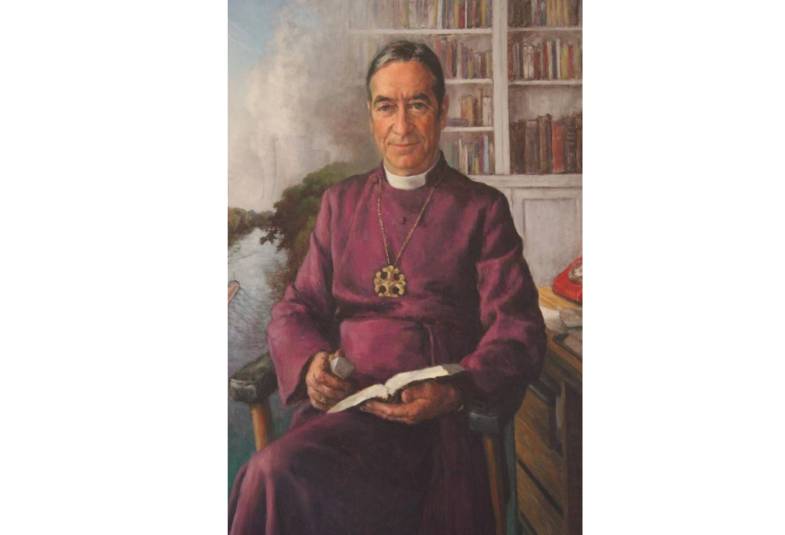

In Bishopthorpe Palace I am surrounded by portraits of my predecessors. Most of them are fairly predictable. One portrait after another depicts an archbishop dressed in convocation robes, seated on some grand throne-like chair, or standing seriously and importantly inside a magnificent building and staring sagely into the middle distance.

Except the portrait of the 94th Archbishop of York, Stuart Blanch.

His portrait is different from all the others.

He isn't wearing any robes, just a simple cassock. And he's not in the church at all.

He is seated at his desk. On the right-hand side of the picture there are some bookshelves. On the left, there is a river and electricity pylons on the horizon. But the river is not ‘outside’ nor the desk and bookshelves ‘inside’. He is in the centre of the painting and inside and outside are dissolving into one another.

On his lap is an open book. We can't see what it is. Only we know. It is the Scriptures. He is somehow suspended between this place of prayer and study and the world in which the fruits of that study and devotion are to be shared.

On this, the last Blanch lecture, and having received the baton from him, I finish with that image of opening the scriptures for the world and of loving the scriptures so much that we are able to listen to the questions and concerns of the world and walk alongside those who ask questions of us, and be drawn to those stories and those words of hope which will speak to the heart of the world’s great need and lead us to a place of encounter with Christ who is the living Word.

For that is how the Emmaus story ends. When they get to Emmaus, Jesus makes as if to go on. Of course, he does. There is always more. And he always waits to be invited in. And even when Cleopas and his companion invite him in to stay, they still don't know who he is.

They invite him because he's good to be with. And he is good to be with his because he listened to them, which we know is always a profound blessing and a gift. And then when he did speak, his words made sense. He spoke with clarity and charity.

Then, the one who was the guest becomes the host. Jesus breaks bread and their eyes are opened.

They then rush back to Jerusalem. The Scriptures have been opened to them. Their hearts are burning. They can’t wait to share with others what they have received. A living word. A word that makes sense. A word that speaks to their hearts.

As we open the scriptures, may we be drawn to do the same.

- 1Paul Ricœur – Hermeneutics of Suspicion

- 2William T. Cavanaugh, Torture and Eucharist: Theology, Politics and the Body of Christ

- 3Lawrence Thornton, Imagining Argentina, from William T. Cavanaugh, Torture and Eucharist

- 4John McIntyre, Faith, Theology and Imagination

- 5Adapted from, Stephen Cottrell, The Things He Said, SPCK

About the Archbishop Blanch Lectures

Stuart Blanch, a former Bishop of Liverpool and later Archbishop of York was a gifted biblical scholar and teacher. His love of scripture and his passion to commend it as a vital element in Christian life and witness marked his numerous books and public speaking.

The annual Blanch Lecture established in his name and honouring his legacy has become an integral and important occasion in the life of the Diocese of Liverpool. Over the years it has brought a wide range of thoughtful and inspiring speakers from within the Church and the academy to engage a large and receptive audience in contemporary issues and how an informed and lively faith might respond to them. Transcripts and videos of previous lectures are available here